Vishnu V – Year 12 Student

Editor’s Note: Year 12 Student Vishnu V considers a big, moral question through multiple different theories. A well researched piece on a discussion that holds a multitude of viewpoints. Vishnu has entered this into the NCH Undergraduate Essay Competition. EB

For an action to be morally correct, it must be the right action and the greater good is when there is an increase in net happiness or utility when the wellbeing of everyone is taken into account in a situation. There are many instances where an innocent person could be sacrificed for the greater good, and does not only pertain to the loss of a life, as sacrifice also means when an individual/s interests are cast aside for an interest that does not suit their own. The main opposition to this is that we have moral obligations that make sacrifice morally unacceptable, regardless of the pain or pleasure as a consequence. While this may seem like an attractive option, that clearly codifies a set of rules to behave upon, the reality of the situation is much more nuanced and requires greater evaluation of the consequences. The question that this title is leading us to explore is whether acting upon the consequences overrule the need for any moral obligations that we set as guidelines for when we make decisions that could involve sacrifice in order to achieve a greater good and I will show why it is morally acceptable to focus on the wider consequences and why strict moral obligations need not be followed to make an action morally acceptable. Rather, the consequences of actions should be used to synthesise a set of rules that we must follow.

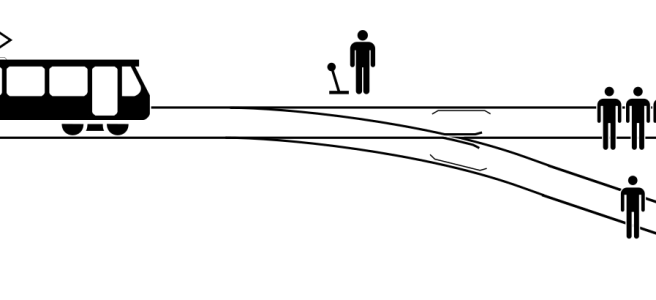

Situations that involve sacrifice inherently require harm towards an individual. This can be captured in the Trolley Problem, wherein an onlooker can save 5 people for the cost of one person’s life. J.S Mill’s Harm principle[1]outlines that power can only be used to prevent harm to others (Mill,2001) [1]. In situations where harm occurs, we must apply a 2 step inquiry (Mill, 2001) and when we apply this to the Trolley Problem, this utilitarian approach leads us to save the 5 people. This brings us to look at autonomous vehicles (AV’s) in the modern world, as vehicles will have to weigh the values of innocent lives in situations of accidents, where a death is unavoidable. Utilitarian theory can be applied to AVs and they can be programmed to choose the option that involves the least damage, and this is a desirable approach as it can be directly quantified (Lin, 2016) [2]. While this could prove a challenge as opposed to deontological approaches, where the AVs follow constant ethical values, this system would have universality and take into account the context of a situation.

Even though a greater good may be caused in the short run due to saving more lives than lost, it is not likely that it will cause more good in the long run.

This is more desirable than a Kantian system that follows a Categorical Imperative, as this system would not take into account any consequence of the aftermath and keeping one innocent person alive could mean 10 other innocent people die. With regards to AVs, this would be morally unacceptable as the majority of AV users would not support this and would hinder development of Avs in society as 90% (Navarrete et al., 2012) [3] of people said they would let the one person die for the greater good of 5 and this clearly contradicts public support for a set law as Kantian ethics would tell us to impose in this situation. Kant’s ethics, which are deontological (Muirhead, 1932) [4], regarding Categorical Imperatives, when applied to the notion of AVs is built upon this argument:

- Moral imperatives cannot have exceptions

- Morality is valid for AVs as they are programmed by rational beings that are subject to agent-relative obligations (Alexander and Moore, 2020) [5]

- Therefore, AVs must not divert their path to harm less people, as to choose to make this decision results in breaking a moral obligation to not choose to harm

If these premises are accepted then it leads us to believe sacrifice can never be allowed in the case of AVs and most other scenarios. However, I would argue that for a situation to be morally acceptable, it must maximise happiness and happiness is good, therefore the greater good cannot be achieved if we do not contextualise these imperatives to a situation. Being inflexible and failing to recognise what is lost in a significant part of the cases in accidents with AVs would not be morally acceptable as the strict rules imposed would lead to a contradiction of the Harm Principle, as greater numbers of people would be harmed, by AV programming that does not fit what the majority want. Consumers may be forced to accept that AVs must be used, whilst having to conform to guidelines the majority of people oppose.

Having examined why not focussing on strict moral obligations on not harming anyone is morally acceptable, it seems logical that we must examine its ethical opposite, why the consequences are important to consider. Consequences need not be the only guideline we look at when making decisions and there can be certain basic tenants that we follow, e.g. ensuring individuals are not harmed when we have the power to end the suffering, without any opportunity cost, however not focussing on the consequences at all has severe ramifications. Applying an agent neutral view to the situation ensures that there are common aims in every situation. This means that there are no exceptions to the rule as decisions are made on the basis of what causes most good for all, this view means that sacrifice is morally acceptable, provided it brings about the greater good.

However, actions and their consequences must not be evaluated individually in each situation, or else liberty and freedom would be stripped from people. A two tiered rule utilitarian system avoids the difficulty of calculating utility in individual situations when sacrifice is involved. Rule utilitarianism is a quasi-rule oriented system[5] and its benefits can be seen as the acceptance of these rules maximise utility. To see the benefits, we can consider a situation wherein a doctor can save 5 lives by harvesting the organs of a healthy human. Even though a greater good may be caused in the short run due to saving more lives than lost, it is not likely that it will cause more good in the long run. If this rule was adapted in society, people would no longer trust doctors meaning the treatment would be of a standard that produces much less happiness. For example, patients may not allow doctors to anaesthetize them, or provide treatment that means they cannot see what is happening as they will not trust the doctors, and thus they will not sacrifice them and jeopardise their liberty. Clearly, this situation would not maximise utility in the long run, even though the greater good is caused in the individual situation. This contradicts the statement that killing one person will maximise utility and this proof by contradiction shows us the need for a set of rules that are adapted, a moral system that the utilitarian principle is applied to. This is relevant as to whether sacrifice is morally acceptable as it would be acceptable if it followed the rules that maximised utility on the large scale considering society as a whole. This is different to a Kantian system, as the rules can be adapted as time goes on and this means that it does not meet the disadvantages of this system I have mentioned above. Moral rules we synthesise based on utility, cannot have exceptions as moral rules are not used here to create net gain of happiness in an individual situation, they are used to limit how we act, even when we look at short run balance of utility, which is hard to judge in situations where sacrifice can occur.

To conclude, sacrifice can be morally acceptable in order to reach some greater good, however we cannot disregard the fact that a system that solely focussed on the good and bad in an individual situation would cause societal disarray and would be impractical. A system based on rules that are not based on harm, but rather utility in the general case of society would mean that individual liberty is not imposed upon, which leads to distrust in society. This would not mean that in the case of AVs they should not sacrifice the one person for the greater good, as in the case of AVs, as a society, we have accepted that they can be used and accepted the nuances in the case of accidents. However as a society, we would object to doctors using anaesthesia to impose on our agency to sacrifice us for the greater good. Ultimately, the rules will determine in what contexts sacrifice is morally acceptable, and the rules will change with what best is suited to make society run without mass disruption. Situations where sacrifice will naturally occur as society develops and it is up to those who are rational to decide to follow societal rules and norms that we make synthesise based on analysis of the long term consequences.

References

- Mill, J.S. (2001). On Liberty Batoche Books Kitchener. [online] Available at: https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/econ/ugcm/3ll3/mill/liberty.pdf.

- Lin, P. (2016). Why Ethics Matters for Autonomous Cars. [online] ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303480862_Why_Ethics_Matters_for_Autonomous_Cars [Accessed 30 Dec. 2022].

- Navarrete, C.D., McDonald, M.M., Mott, M.L. and Asher, B. (2012). Virtual morality: Emotion and action in a simulated three-dimensional ‘trolley problem’. Emotion, [online] 12(2), pp.364–370.

- Muirhead, John H. 1932. Rule and End in Morals. London: Oxford University Press.

- Alexander, L. and Moore, M. (2020). Deontological Ethics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). [online] Stanford.edu. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-deontological/#WeaDeoThe [Accessed 31 Dec. 2022].

[1] “The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

[2] “Harm is necessary in some scenarios, where utility in the long run is derived from the action and in these situations, a utilitarian approach is applied to measure the consequences. Mill said “Whoever succeeds in an overcrowded profession, or in a competitive examination; whoever is preferred to another in any contest for an object which both desire, reaps benefit from the loss of others, from their wasted exertion and their disappointment. But it is, by common admission, better for the general interest of mankind, that persons should pursue their objects undeterred by this sort of consequences.” This tells us that actions that cause harm in the short term, are acceptable if the actions produce a result better for the majority in the situation.

[3] Deontological theories hold that there are ethical propositions of the form: “Such and such a kind of action would always be right (or wrong) in such and such circumstances, no matter what its consequences might be.”

[4] “An agent-relative obligation is an obligation for a particular agent to take or refrain from taking some action; and because it is agent-relative, the obligation does not necessarily give anyone else a reason to support that action.”

[5] “Rules play a crucial role, however the system is based on a principle that happiness must be maximised in the general case and in the long run in this case. The basic utilitarian rule of maximising happiness is used, however takes into account social interactions, to synthesise a system of rules that maximise happiness in society.”