Tehan (Year 12)

Editor’s note: Year 12 student Tehan, now in Year 13, wrote this essay for submission to the FCDO Next Generation Economics 2025 competition. They chose to answer the question: While free trade has been the dominant view in the last decades, protectionist policies are on the rise. What are the drivers of the global moves away from free trade and how should the UK respond? Pleasingly, out of over 800 entries, Tehan’s submission was recognised in the top eight of all entries received. As the judges note, “The candidate did well to consider the UK’s position in the global trade debate as a service based economy in contrast to some European partners. The letter also analysed the political drivers of the shift towards protectionism as well as the economic drivers. It would have been helpful if the candidate had demonstrated their understanding of economic theory a bit more in the letter which would have also strengthened their argument.” Tehan wins a visit to LSE and the FCDO in London, prize money of £100, and a free book from a shortlist selected by the FCDO Chief Economist. CPD

Dear Rt Hon David Lammy MP,

The free trade consensus that defined the early 21st century is fracturing. From the COVID-19 shock to the Russia-Ukraine war, and the resurgent Trump tariffs, global trade tensions have reignited. In 2025 alone, over 3500 harmful trade interventions were implemented globally [Global Trade Alert, 2025]. This letter argues that the three core drivers: industrial strategy, geopolitical risk, and populist politics, are fuelling the retreat from free trade, and that the UK must respond with a balanced and pragmatic strategy. I offer three distinct proposals. Strengthen bilateral FTAs, support strategic sectors, and capitalise on the UK’s comparative advantage in services.

The primary driver that is fuelling protectionist policies is the strategic aim to shield and nurture domestic industries that are undermined by more competitive foreign producers. Governments across the world are increasingly using trade barriers to enable domestic firms to scale up, to ultimately develop economies of scale and eventually become more internationally competitive. This aligns with the infant industry argument [Kenton W. 2023], which posits that nascent sectors require temporary protection to survive and grow in the short term, so they can compete globally in the long term once they have overcome cost disadvantages and productive inefficiencies. Moreover, when foreign producers possess comparative advantages, such as China, which benefits from cheaper labour and technological superiority [Rajput, A. 2024], allowing it to undercut US entrants, making it more difficult for emerging industries to survive without protectionism. Trump’s tariffs exemplify protectionist measures to raise the market price to cut imports, such as the 145% tariff on China [Lovely et al., 2025] to raise US output from Q1 to Q3 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 [Reed, J. 2024]

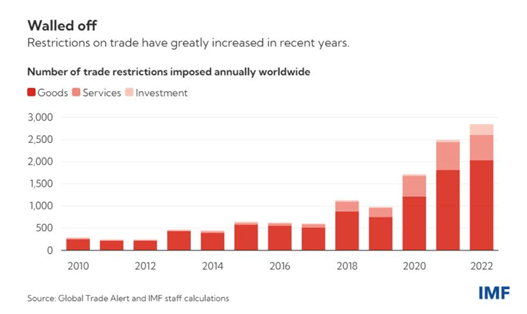

In a world marked by rising geopolitical risk, as seen with the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, the fragility of global supply chains with the UK PPE crisis [National Audit Office, 2020] and Western dependence on Russian oil [Appunn, K. 2022] have been exposed. This has led to a surge in protectionist measures (see Figure 2) to guarantee an uninterrupted supply of goods and services in national crises. The United States, for example, pursued domestic reindustrialisation through the CHIPS and Science Act 2022 [Teer, J. and Bertolini, M. 2022], allocating $52.7 billion in subsidies to reverse their sharp decline in domestic semiconductor production which has fallen from nearly 40% of global capacity in 1990 to just 12% by 2022 [PwC, 2023]

Figure 2 [IMF, 2023]

Populism frames foreign trade as threats to national and economic security and uses protectionism to take back control. From the rise of populist leaders such as Farage or President Trump, countries are increasingly turning to tariffs, quotas, and departures from multilateral trade agreements. The aftermath of Brexit boosted protectionist measures through, for example, the National Security and Investment Act 2021 [Levitt, M. et al. 2021]. Populism has appealed to voters in deindustrialised regions who perceive themselves as victims of globalisation and free trade. The inevitability of protectionist measures following populist prioritisation of national sovereignty is proven under Rodrik’s political trilemma, in which globalisation and free trade ceases to exist when national sovereignty and democracy are prioritised [Rodrik, D., 2011].

Strengthening bilateral trade deals is crucial in responding to widespread protectionist measures. Not only will this be tangibly beneficial for the economy, but it also symbolically shows the strength of free trade and the inefficiency of protectionism. The UK-India FTA in May 2025, which has mutually cut tariffs and removed trade barriers, is reported to boost the UK economy by £4.8 billion by 2040 [Assomull, S. 2025]. This symbolic deal likely furthered the case for the UK-US trade deal, which removed the 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium among other measures [UK Government, 2025]. Furthering bilateral trade deals with fast-growing economies such as Brazil and South Africa will grow the UK economy and push foreign countries to ease off protectionist measures after realising the prosperity from free trade.

It is important to note that the fundamental reason why protectionist measures are inefficient is because it leads to reduced innovation and creativity, key forms of X-inefficiency, [Leibenstein, H. 1966] from domestic producers due to complacency after government protection and a lack of international competition. The motive behind protectionism was to protect infant industries and small firms until they can compete on global markets, but instead, this can be achieved through targeted supply-side policies by investing in R&D, building new infrastructure, and upskilling workers – this is essential since the UK’s skill gap is one of the worst in the OECD [IFS, 2023]. This in turn will promote national resilience while preserving the benefits from free trade.

The UK is a service-based economy, consistently running a trade in services surplus and trade in goods deficit for more than 4 decades (see Figure 3). While focusing on stabilising declining manufacturing sectors is important, a greater priority should be to lean into UK’s comparative advantage in high-value service exports such as law, finance, education, fintech, and digital services [Stojanovic, A. 2019]. One innovative approach is to establish ‘Digital Freeports’: virtual zones that have bespoke regulatory and tax frameworks where digital services can be traded across borders with reduced friction. Such zones would protect the UK from rising goods-based protectionism, like tariffs and quotas, by shifting trade into the digital world. As trade economist Richard Baldwin argues, the “third unbundling” of globalisation, which refers to the rise in workers in one nation being able to provide services in another nation, is already underway [Baldwin, R. 2016]. The UK should institutionalise this shift, not resist it.

Figure 3 [House of Commons Library, 2018]

Overall, I believe these policy measures will effectively protect the economic prosperity of the UK, and lead by example to protect against further protectionism. By strengthening bilateral FTAs, investing in targeted supply-side reform, and leaning into UK’s comparative advantage in services through the proposed Digital Freeports, the impact of rising protectionism would be alleviated in the short and long-term, and guarantee economic prosperity.

Yours sincerely,

XX

Bibliography

Appunn, K. 2022. The practical challenges of an embargo on Russian oil. Clean Energy Wire, 14 April. Available at: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/practical-challenges-embargo-russian-oil

Assomull, S. 2025. What the India-UK trade agreement means for fashion. Vogue Business, 8 May. Available at: https://www.voguebusiness.com/story/consumers/what-the-india-uk-trade-agreement-means-for-fashion

Baldwin, R. 2016. Globalization’s Three Unbundlings. Harvard University Press Blog, 29 November. Available at: https://harvardpress.typepad.com/hup_publicity/2016/11/globalizations-three-unbundlings.html

Global Trade Alert. (2025). GTA Data Centre. [online] Available at: https://www.globaltradealert.org/data-center [Accessed 10 May 2025].

Institute for Fiscal Studies. 2023. Investment in training and skills. In: Emmerson, C., Farquharson, C. and Stockton, I. (eds), The IFS Green Budget: October 2023. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-10/IFS-Green-Budget-2023-Investment-in-training-and-skills.pdf

International Monetary Fund. 2023. The high cost of global economic fragmentation. The Business Standard, 29 August. Available at: https://www.tbsnews.net/world/global-economy/high-cost-global-economic-fragmentation-imf-690834

Kenton, W. 2023. Infant-Industry Theory: Definition, Main Arguments, and History. Investopedia, updated 8 September. Reviewed by Robert C. Kelly. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/infantindustry.asp

Leibenstein, H. 1966. Allocative Efficiency vs. “X-Efficiency”. The American Economic Review, 56(3), pp.392–415. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1823775

Levitt, M., Beaumont, S.J., and Wilcox, J. 2021. Protectionism vs free trade in the UK. Financier Worldwide, January. Available at: https://www.financierworldwide.com/protectionism-vs-free-trade-in-the-uk

Lovely, M.E., Bora, S.I. and Simon, L. 2025. Destined for Division? US and EU Responses to the Challenge of Chinese Overcapacity. Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief 25-2, 24 April. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5234115 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5234115

National Audit Office, 2020. The supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 pandemic. HC 961, Session 2019–2021, 25 November 2020. London: National Audit Office. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk

PwC. 2023. The CHIPS Act: What it means for the semiconductor ecosystem. Available at: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/semiconductors/chips-act.html

Rajput, A. 2024. “Made in China” – Why Does China Produce So Much? Discover Economics, 19 April. Updated 13 May. Available at: https://www.discovereconomics.co.uk/post/made-in-china-why-does-china-produce-so-much

Reed, J. 2024. 4 Keys to Trade and Tariff Graphs. ReviewEcon.com, updated 22 March. Available at: https://www.reviewecon.com/trade-tariffs

Rodrik, D. 2011. The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company. Available at: https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/publications/globalization-paradox-democracy-and-future-world-economy

Stojanovic, A. 2019. Trade: services. Institute for Government, 15 May. Available at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/explainer/trade-services

Teer, J. and Bertolini, M. 2022. Chapter 3: Winning interdependence: semiconductor and CRM rivalry in a de-globalising world. In: Reaching Breaking Point: The Semiconductor and Critical Raw Material Ecosystem at a Time of Great Power Rivalry. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep44057.8

UK Government. 2025. Landmark economic deal with United States saves thousands of jobs for British car makers and steel industry. GOV.UK, 8 May. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/landmark-economic-deal-with-united-states-saves-thousands-of-jobs-for-british-car-makers-and-steel-industry

Ward, M., 2018. UK trade in 2017. House of Commons Library, 6 August. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/uk-trade-in-2017/ [Accessed 10 May 2025].